Regency Weddings

The Honour of your presence is requested ...

How long was a betrothal during the Regency? Did the bride carry flowers or wear a veil? What did wedding dresses look like?

First things first. Just like today, there were laws regarding marriage and these sorts of boring details must be attended to before one goes about planning the fun stuff.

The Marriage Act

Before 1753, couples in England could legally marry without clergy, church, or signing a record: a simple exchange of vows did the trick, so long as two witnesses were present and both couples were of marrying age: fourteen for men, twelve for women. Egad! These sorts of weddings were nicknamed Fleet Marriages, because many marriages came about in Fleet Prison, a debtor’s prison.

With the Marriage Act of 1753, a few things changed. Both parties had to be 21 or have parental consent to marry. In addition, the Banns were required to be read or the couple needed to procure a license to be legally married (in England or Wales, that is. More on Scotland later.) The wedding must take place before noon; the bride or groom must reside in the parish where the ceremony was held; witnesses were required; the wedding must be performed by a member of the clergy in a Church of England parish, Quaker meeting, or Jewish synagogue; and the wedding had to be recorded in the marriage register with the signatures of both parties, witnesses, and clergyperson.

During the Regency, there was more than one way to shackle a leg, so to speak: through reading the Banns, by common license, by special license, or elopement.

The Banns

Imagine how exciting it must have been for the bride- and groom-to-be: right after the Offertory during Divine Services, the vicar would have announced the Marriage Banns:

I publish the Banns of marriage between [Groom's Name] of [his local parish] and [Bride's Name] of [her local parish]. If any of you know cause or just impediment why these two persons should not be joined together in Holy matrimony, ye are to declare it. This is the first [second, third] time of asking.

For three consecutive Sundays or Holy Days, the Banns were read during the service. If the bride and groom attended different parishes, the Banns were read in both. The Banns were valid for three months, but could be read again.

Therefore, the minimum amount of time required for an engagement was three weeks. Lengthy betrothals tended to occur because of money: Cassandra Austen's long engagement provided time for her betrothed, Thomas Fowle, to earn sufficient funds for them to live comfortably. Unfortunately, he passed away while serving as a military chaplain in the Caribbean before they could marry.

Common License

Not every couple found the reading of the Banns romantic or exciting. Some found it downright common (gasp!). If a couple wished—or needed—to marry without waiting a few weeks for the banns to be read, once could procure a Common (or Bishop’s) License for the cost of ten shillings. Because it cost money, sometimes the upper classes procured a license just because they could. If the bride or groom were under age 21, parental consent was required. The license was valid for three months, and a wedding must take place in a church where one member of the couple attended.

Special License

This is certainly the most dramatic of the legal options. It required a good deal of money (five pounds) and the ability to obtain the license from the Archbishop of Canterbury. I've read one also had to be a peer or peeress, the child of a peer, a baronet, knight, member of Parliament, a Privy Counselor or Westminster Court Judge to obtain one, although I don't know if this was a hard and fast rule. I imagine it had a lot to do with the Archbishop not being accessible to just anyone. With a Special License, the bride and groom could marry anywhere (such as at home), at any time of day, in haste and privacy, if they wished. All other requirements were the same: witnesses and parental consent for minor parties were required. In Pride and Prejudice, Mrs. Bennet crows that Lizzie and Mr. Darcy will be married by special license, referencing his wealth. In any case, he and Lizzie enjoyed a double wedding with Jane and Bingley.

Let’s Elope!

The Marriage Act of 1763 did not apply to Scotland. In the Church of Scotland, a couple did not require clergy to pronounce them husband and wife: their exchange of promise before witnesses was legally sufficient.

Just north of the English border, an industry grew to provide legal wedding ceremonies for those who did not have parental consent. Lamberton, Mordington, and Coldstream Bridge were all “Border Villages” known for offering quick weddings, but none were as famous as Gretna Green, a small village on the old coaching road between London and Edinburgh.

Many couples wed at the blacksmith’s shop, forging the phrase “over the anvil” (yes, it’s a terrible pun). Inns also served as wedding chapels, and small (ahem) bedrooms were located at many marriage hot-spots; should the bride be pursued by her furious family, the marriage could be consummated quickly. The law changed in 1856, requiring a 21-day residency for marriages.

It should be noted that for those desiring a church wedding in Scotland, banns were read in the Kirk for three successive weeks, too, just like in England. For a fee, however, all three banns could be read on one Sunday, thus speeding up the process.

For those not running away to wed, there were formalities to follow, details to consider, and fun plans to make. Some of them carry on to present day!

How long was a betrothal during the Regency? Did the bride carry flowers or wear a veil? What did wedding dresses look like?

First things first. Just like today, there were laws regarding marriage and these sorts of boring details must be attended to before one goes about planning the fun stuff.

The Marriage Act

Before 1753, couples in England could legally marry without clergy, church, or signing a record: a simple exchange of vows did the trick, so long as two witnesses were present and both couples were of marrying age: fourteen for men, twelve for women. Egad! These sorts of weddings were nicknamed Fleet Marriages, because many marriages came about in Fleet Prison, a debtor’s prison.

With the Marriage Act of 1753, a few things changed. Both parties had to be 21 or have parental consent to marry. In addition, the Banns were required to be read or the couple needed to procure a license to be legally married (in England or Wales, that is. More on Scotland later.) The wedding must take place before noon; the bride or groom must reside in the parish where the ceremony was held; witnesses were required; the wedding must be performed by a member of the clergy in a Church of England parish, Quaker meeting, or Jewish synagogue; and the wedding had to be recorded in the marriage register with the signatures of both parties, witnesses, and clergyperson.

During the Regency, there was more than one way to shackle a leg, so to speak: through reading the Banns, by common license, by special license, or elopement.

The Banns

Imagine how exciting it must have been for the bride- and groom-to-be: right after the Offertory during Divine Services, the vicar would have announced the Marriage Banns:

I publish the Banns of marriage between [Groom's Name] of [his local parish] and [Bride's Name] of [her local parish]. If any of you know cause or just impediment why these two persons should not be joined together in Holy matrimony, ye are to declare it. This is the first [second, third] time of asking.

For three consecutive Sundays or Holy Days, the Banns were read during the service. If the bride and groom attended different parishes, the Banns were read in both. The Banns were valid for three months, but could be read again.

Therefore, the minimum amount of time required for an engagement was three weeks. Lengthy betrothals tended to occur because of money: Cassandra Austen's long engagement provided time for her betrothed, Thomas Fowle, to earn sufficient funds for them to live comfortably. Unfortunately, he passed away while serving as a military chaplain in the Caribbean before they could marry.

Common License

Not every couple found the reading of the Banns romantic or exciting. Some found it downright common (gasp!). If a couple wished—or needed—to marry without waiting a few weeks for the banns to be read, once could procure a Common (or Bishop’s) License for the cost of ten shillings. Because it cost money, sometimes the upper classes procured a license just because they could. If the bride or groom were under age 21, parental consent was required. The license was valid for three months, and a wedding must take place in a church where one member of the couple attended.

Special License

This is certainly the most dramatic of the legal options. It required a good deal of money (five pounds) and the ability to obtain the license from the Archbishop of Canterbury. I've read one also had to be a peer or peeress, the child of a peer, a baronet, knight, member of Parliament, a Privy Counselor or Westminster Court Judge to obtain one, although I don't know if this was a hard and fast rule. I imagine it had a lot to do with the Archbishop not being accessible to just anyone. With a Special License, the bride and groom could marry anywhere (such as at home), at any time of day, in haste and privacy, if they wished. All other requirements were the same: witnesses and parental consent for minor parties were required. In Pride and Prejudice, Mrs. Bennet crows that Lizzie and Mr. Darcy will be married by special license, referencing his wealth. In any case, he and Lizzie enjoyed a double wedding with Jane and Bingley.

Let’s Elope!

The Marriage Act of 1763 did not apply to Scotland. In the Church of Scotland, a couple did not require clergy to pronounce them husband and wife: their exchange of promise before witnesses was legally sufficient.

Just north of the English border, an industry grew to provide legal wedding ceremonies for those who did not have parental consent. Lamberton, Mordington, and Coldstream Bridge were all “Border Villages” known for offering quick weddings, but none were as famous as Gretna Green, a small village on the old coaching road between London and Edinburgh.

Many couples wed at the blacksmith’s shop, forging the phrase “over the anvil” (yes, it’s a terrible pun). Inns also served as wedding chapels, and small (ahem) bedrooms were located at many marriage hot-spots; should the bride be pursued by her furious family, the marriage could be consummated quickly. The law changed in 1856, requiring a 21-day residency for marriages.

It should be noted that for those desiring a church wedding in Scotland, banns were read in the Kirk for three successive weeks, too, just like in England. For a fee, however, all three banns could be read on one Sunday, thus speeding up the process.

For those not running away to wed, there were formalities to follow, details to consider, and fun plans to make. Some of them carry on to present day!

Invitations

Unlike the mass-produced invitations of today, guests were invited to the wedding through personal correspondence. Writing multiple letters must have taken quite some time, but one’s guest list was quite small compared to today’s standards, limited to family and close friends. When the Prince of Wales married (before he became Regent), only a few people witnessed the event.

Bridesmaids

The existence of bridesmaids goes back to medieval times, and they were often involved in Regency weddings. Jane Austen’s niece Anna married in 1814, and her bridesmaids were the groom’s sisters, children who wore white dresses and straw bonnets. Not only children served as bridesmaids, however. In Emma, Jane Austen writes “Emma attended Harriet to church, and saw her hand bestowed on Robert Martin.” In attending Harriet, it’s clear Emma isn’t just a wedding guest.

However, the notion of multiple bridesmaids standing beside the bride while wearing matching dresses didn't start until the Victorian period.

Unlike the mass-produced invitations of today, guests were invited to the wedding through personal correspondence. Writing multiple letters must have taken quite some time, but one’s guest list was quite small compared to today’s standards, limited to family and close friends. When the Prince of Wales married (before he became Regent), only a few people witnessed the event.

Bridesmaids

The existence of bridesmaids goes back to medieval times, and they were often involved in Regency weddings. Jane Austen’s niece Anna married in 1814, and her bridesmaids were the groom’s sisters, children who wore white dresses and straw bonnets. Not only children served as bridesmaids, however. In Emma, Jane Austen writes “Emma attended Harriet to church, and saw her hand bestowed on Robert Martin.” In attending Harriet, it’s clear Emma isn’t just a wedding guest.

However, the notion of multiple bridesmaids standing beside the bride while wearing matching dresses didn't start until the Victorian period.

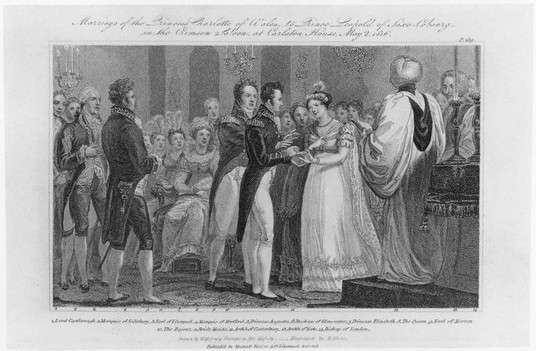

1818 Engraving of the marriage of Princess Charlotte and Prince Leopold. Public domain.

The Bridal Gown

The idea of a white-gowned lady in a veil is Victorian. In the Regency, a bride could wear any color or pattern. In the latter part of the 1700s, blue, white and silver were favored colors for weddings, but light-colored gowns of other hues grew in popularity by the early 1800s—for wealthier brides. Since these gowns would be worn again and again, brides of lower social circles would often choose their best gowns or something dark and practical.

As the gowns were re-worn, brides tended to cherish another part of their costume: their shoes. Brides sometimes described their weddings on slips of paper and placed them in their slippers.

Regency brides wore bonnets or caps through the ceremony, although in Emma, veils are referenced, but tantalizingly so: Austen does not describe who is wearing them.

The most famous Regency wedding gown, of course, was that of Princess Charlotte to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (or as she called him, “The Leo”) in May of 1816. The bride wore silver lama over a silver tissue slip, embroidered with silver shells and flowers. The sleeves were trimmed in point Brussels lace, and the manteau was silver tissue, fastened with a diamond.

Note in the engraving, no flowers are shown. No flowers are mentioned in contemporary descriptions of Princess Charlotte's wedding.

The idea of a white-gowned lady in a veil is Victorian. In the Regency, a bride could wear any color or pattern. In the latter part of the 1700s, blue, white and silver were favored colors for weddings, but light-colored gowns of other hues grew in popularity by the early 1800s—for wealthier brides. Since these gowns would be worn again and again, brides of lower social circles would often choose their best gowns or something dark and practical.

As the gowns were re-worn, brides tended to cherish another part of their costume: their shoes. Brides sometimes described their weddings on slips of paper and placed them in their slippers.

Regency brides wore bonnets or caps through the ceremony, although in Emma, veils are referenced, but tantalizingly so: Austen does not describe who is wearing them.

The most famous Regency wedding gown, of course, was that of Princess Charlotte to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (or as she called him, “The Leo”) in May of 1816. The bride wore silver lama over a silver tissue slip, embroidered with silver shells and flowers. The sleeves were trimmed in point Brussels lace, and the manteau was silver tissue, fastened with a diamond.

Note in the engraving, no flowers are shown. No flowers are mentioned in contemporary descriptions of Princess Charlotte's wedding.

Poshest place to wed: St. George's, Hanover Square, by T. Malton, 1787. Public Domain

With This Ring

Placing a ring on the bride’s fourth finger of her left hand was part the wedding service. In a promise that makes my heart pitter-patter, the groom said this:

With this Ring I thee wed, with my body I thee worship, and with all my worldly goods I thee endow: In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

The ring could be made of any metal, although gold was preferred. The groom did not wear a wedding ring.

Engagement rings as we know them were not in vogue, although a ring could be given as a symbol of affection—by men and women, particularly in the case of a lengthy engagement. In Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, Edward wears a ring made of his fiancée’s hair. (Hair rings/tokens/wreaths were not unusual in the nineteenth century, a practice which seems odd today.)

Here Comes the Bride

“Dearly beloved, we are gathered together here in the sight of God….”

Much of the ceremony would be recognizable to contemporary North Americans, as the Book of Common Prayer’s liturgy has been adopted by many denominations. The vicar described the purpose of the gathering and explained God’s purpose for matrimony. He charged the bride and groom to confess any impediment which might prevent them from lawfully being married. Vows are exchanged to “have and to hold from this day forward … thereto I plight thee my troth.” Prayers, a blessing, Scripture readings, and a homily are also included in the wedding service.

To read the complete service, follow the link to the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

Let’s Celebrate!

Troths were been pledged, lives were joined, but before leaving the church, the couple signed the registry (the bride signed her maiden name, which has served to help those of us with genealogical hobbies).

Since weddings were over by noon, the celebratory meal was called a breakfast (Regency breakfasts were eaten between 10-1, sort of like brunch). While the wealthy might enjoy a heartier meal, the standard breakfast consisted of rolls, toast, eggs, ham, bacon or tongue, perhaps a fish, tea, chocolate (not sweet like hot chocolate of today) and a wedding cake.

The cake was probably more like a dense fruitcake than we eat today. Like bridesmaids and rings, cakes were already a long-standing wedding tradition, and probably symbolized fertility once upon a time.

Happily Ever After

If the couple could afford a honeymoon, or bridal tour, they would set off into the sunset in their carriage, full of dreams and hopes for their brilliant future and houseful of children.

Placing a ring on the bride’s fourth finger of her left hand was part the wedding service. In a promise that makes my heart pitter-patter, the groom said this:

With this Ring I thee wed, with my body I thee worship, and with all my worldly goods I thee endow: In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

The ring could be made of any metal, although gold was preferred. The groom did not wear a wedding ring.

Engagement rings as we know them were not in vogue, although a ring could be given as a symbol of affection—by men and women, particularly in the case of a lengthy engagement. In Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, Edward wears a ring made of his fiancée’s hair. (Hair rings/tokens/wreaths were not unusual in the nineteenth century, a practice which seems odd today.)

Here Comes the Bride

“Dearly beloved, we are gathered together here in the sight of God….”

Much of the ceremony would be recognizable to contemporary North Americans, as the Book of Common Prayer’s liturgy has been adopted by many denominations. The vicar described the purpose of the gathering and explained God’s purpose for matrimony. He charged the bride and groom to confess any impediment which might prevent them from lawfully being married. Vows are exchanged to “have and to hold from this day forward … thereto I plight thee my troth.” Prayers, a blessing, Scripture readings, and a homily are also included in the wedding service.

To read the complete service, follow the link to the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

Let’s Celebrate!

Troths were been pledged, lives were joined, but before leaving the church, the couple signed the registry (the bride signed her maiden name, which has served to help those of us with genealogical hobbies).

Since weddings were over by noon, the celebratory meal was called a breakfast (Regency breakfasts were eaten between 10-1, sort of like brunch). While the wealthy might enjoy a heartier meal, the standard breakfast consisted of rolls, toast, eggs, ham, bacon or tongue, perhaps a fish, tea, chocolate (not sweet like hot chocolate of today) and a wedding cake.

The cake was probably more like a dense fruitcake than we eat today. Like bridesmaids and rings, cakes were already a long-standing wedding tradition, and probably symbolized fertility once upon a time.

Happily Ever After

If the couple could afford a honeymoon, or bridal tour, they would set off into the sunset in their carriage, full of dreams and hopes for their brilliant future and houseful of children.